Was Jimi Hendrix a Musician?

It made the national press some five years ago, but then it seemed to get allocated to the 'too hard basket'. Medical students at the nation's universities receiving only a fraction of the time usually spent studying basic anatomy. Response from training schools predictably objected to the scrutiny, explained that the medical curriculum was now broader and more congested and besides, there were improved virtual training facilities. The issue faded but I remained concerned the public would not accept a new medico being au fait on gender issues in drug trials, but vague on where the vagus nerve is.

This week, another education issue surfaces in the National media that would cause just as much incredulity as the medical revelations. Tertiary graduates of music courses who cannot read music. My initial reaction to this disclosure is that this is comparable to a swimmer who can’t swim. Surely not, wouldn’t the skill be axiomatic to being able to function in this industry. As 80% of graduates in these courses end up in some form of teaching, to be able to interpret, change and play a music score would be a foundation skill. Well that is the conventional wisdom, but what is conventional is under challenge and some aspects of the new thinking make sense.

Peter Tregear, former head of the ANU school of music, points out that students can graduate from music degrees without being able to read music. In particular, this applies to studies of contemporary music and music technology. Tregear’s explanation as to why we have this gathering trend in tertiary music courses would indeed make you weep.

”He attributes the decoupling of music education and traditional notation to the march of new technologies and – more controversially – to a push to 'decolonise' the music curriculum, because the classical canon was largely created by dead white men.’’

Tregear, obtained a PhD in musicology from Cambridge University and has worked at Cambridge, Melbourne and Monash Universities. “It’s a misunderstanding of what universities are there to do. We’re meant to be expanding minds and opening horizons.… If you no longer teach musical notation, you effectively wipe out not just a good deal of recent Australian music history, but a large swathe of music history full-stop.’’

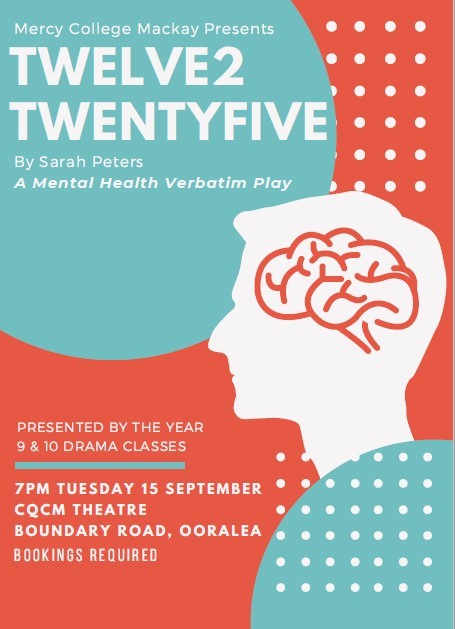

Others, however, think the conventional approach to music education is outdated. Technology has definitely revolutionised the sector with software able to develop a music score from the author essentially simply humming a tune. The new courses are popular, attracting record enrolments. Auditions for students specialising in music software are very different from those specialising in classical composition. Interestingly though, true expertise seems to belong to those who have a foot in both camps. This includes our secondary teachers specialising in music education. Miss Rossetto is building music numbers at Mercy through the broader appeal, with compilation software like ‘Garage Band’ and an engaging variety of learning experiences in addition to music theory.

Critics may also have a point that music traditions, other than western classical, exist and deserve some attention. Kim Cunio who now leads the ANU music school, believes in traditional music theory but also advocates for ‘decolonising’ the music curriculum. This includes the study of music from Asia, Africa and the Middle East that only has an oral tradition. He believes the real threat to music is to go down the popular music route. However, even this musical sector is contentious with the auditory tradition being the mechanism where some of the most famous composers specialised. Sir Paul McCartney, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Michael Jackson could not read or write music but had extraordinary abilities to excel in popular music. The modern music school would consider auditory learning an undervalued skill and a way of engaging many more young people who consider music theory and script sterile and difficult to master.

Despite the disappointing political motivations of some music academics to champion ‘cancel culture’ and deny the obvious artistry and sophistication of the western canon, it would appear the modern study of music has good cause to broaden the education profile beyond the traditional approaches. The new music professional has more than 'one string to their bow'.

ANU PhD composition student Roya Safaei brings a mash-up of old disciplines and new approaches to her studies. She plays classical piano and also studies traditional Persian music, in which time-honored pieces are passed down through observation and listening. “There is really no notation, and improvisation is highly prized,’’ explains Safaei.

Add to this the contemporary skills of modern music software to manipulate and refine original compositions, you have a versatile and highly skilled contemporary musician. Few would doubt the ability to read and write music is not central to this skillset, but mastering diverse influences is now central to graduating new music professionals.

Mr Jim Ford

Source: The Weekend Australian August 29-30, 2020 ‘Notes on a scandal – Face the music’ by Rosemary Neill